- 签证留学 |

- 笔译 |

- 口译

- 求职 |

- 日/韩语 |

- 德语

Linguists and translation theorists

In its concern with the study of language, linguistics has produced numerous theories about how language works. As a language activity, translation can be seen as part of linguistics. Thus a theory of translation drawn from linguistic theory must be viewed as a logical outcome (see also Catford 1965). For example, by studying linguistics it can be shown how language varies in relation to social status, age, gender and so on, and this can help to inform translation decisions. The relationship between linguistics and translation theory could, however, be more mutually beneficial, something that has continued to be reflected in the literature (Fawcett 1997: 1-2). This was anticipated by Bell (1991: xv, 21) when he pointed out that translation theorists had made limited use of

the techniques and insights of contemporary linguistics and, at times, have demonstrated their lack of understanding of the principles of linguistics and its methods of investigation. Linguists, on the other hand, have been either neutral or, at times, even hostile to the notion of a theory of translation because they have failed to fully understand its objectives and methods.

The concept of translation as a 'science' and at the same time, an 'art' or 'craft', may have something to do with the view held by some linguists. The notion that translation is a 'science', or perhaps a 'discipline', is acceptable to linguists, who strive to make objective observations and descriptions of linguistic phenomena. It is the notion of translation as an 'art'or 'craft', as influenced by literary theory and criticism, philosophy and rhetoric, with the creative aspect as the focal point in translation (see also Savory 1968; Biguenet and Schulte 1989) that is a notion less easily embraced by linguists, as it is not open to objective description and explanation. As a result of these contradictory views, a theory of translation is often not taken seriously (Bell 1991: 4).

Linguists and scientists

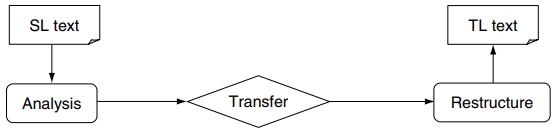

Another group that exists almost independently of the ones discussed above are the 'scientists', including computer scientists, language engineers and computational linguists, who write computer programs and use linguistic theories to develop the language component of machine translation systems. Computational scientists have applied linguistic theories to enhance the performance of machine translation systems because linguistics offers 'a range of observations, techniques and theories that may be adopted and extended within the MT [machine translation] enterprise' (Bennett 2003: 157). However, scientists do not in general contribute to the body of linguistic and/or translation literature. Acknowledgements or references to translation theory are also scarce even in relation to the architectures of rule-based machine translation systems, which contain linguistic applications (see Chapter 3). Although rule-based architectures rely on linguistic approaches, they also resemble the three-step translation process introduced by Nida (1969: 484) as illustrated in Figure 1.

SL =source language; TL = target language

Figure 1 Translation process model

Source: Nida (1969): 484.

For the scientist, the main issue is not whether linguistics is prescriptive or descriptive; a more important criterion is that the particular approach applied must be computationally tractable (Bennett 2003: 144). This means that to be useful to the building of a machine translation system, the computer program implementing the linguistic approach must run at a practical or acceptable speed on a standard computer. Linguists, on the other hand, are more interested in language from a human perspective and since many obstacles are encountered in the process of studying and describing a single language, it is not in their interest to even consider studying and describing two languages involving translation. This is compounded by their misconception (like many others) of the real purpose of the development of machine translation systems (Hutchins 1979: 29), which is not to replace human translators.

In the absence of a real human brain which can provide immediate insights into the processing and generation of texts, to the scientist, machine translation is a good alternative that can be used to test linguistic theories through simulation. However, the reluctance of linguists to venture into experimenting with simulating brain processes via machines may be due to the fact that there are still many uncertainties as to what goes on in the brain. As speakers of a language, linguists can always rely on their own intuitions about what is correct or grammatical and what is not in order to conduct linguistic testing. This is based on the assumption that a language user must 'know' the 'rules' of his/her language system in order to use it. The user also 'knows' when

mistakes are made. The same, however, does not apply to a machine translation system. The programming code is at best 'readable', that is the machine can read and execute it, but it is not capable of 'understanding' its purpose. Since the first attempt more than fifty years ago at building a machine translation system, translation problems such as lexical and syntactic ambiguities still have to be solved.

责任编辑:admin