Following this overview of the approach to game localization undertaken at Square Enix, this section cites a number of specific examples which we consider to demonstrate the company's wholesale readiness to transform their products through the localization process, involving innovation and appropriation, in terms of translation norms established by other forms of translation.

1. Use of icon and voice replacing original written text

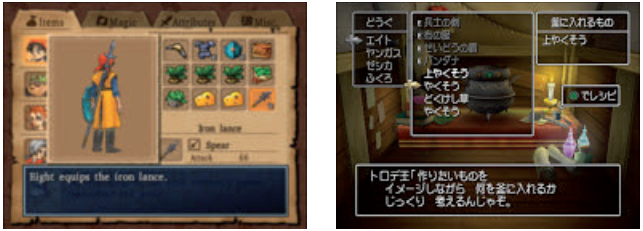

The English localized versions of Square Enix's flagship series Dragon Quest VIII (2004) (see Figure 4.1) introduced the use of icons, which replaced the original text-based menu system and aimed to make the localized version user-friendly. A game reviewer’s comment indicates that the solution served the purpose as he remarks: “Square Enix has taken great care in going back into the Japanese code and has streamlined the menu system to be cleaner and more accessible for US gamers" (Dunham 2005).

This illustrates the approach to localization by Square Enix as unreservedly target-oriented, which also alleviates problems of space constraints. The same game also shows an innovative localization approach, using voiced dialogue to replace the original written dialogue. In localized versions of this game, the original written Japanese dialogues were voiced into English. Yuji Horii, the game's creator, explains that this was considered a better way of conveying characters' emotions in localized versions, whereas written text was sufficient for Japanese gamers to fully appreciate the nuances of the intended effect (cited in Onyett 2005). This suggests that isosemiotic translation (Gottlieb 2004, 86) – i.e. translation using the same communication channel, in this case from written to written form – was not considered to be sufficient to create an equivalent affective result between the original game and the source language player, and the localized game and the target player. This case demonstrates the extended scope of localization affording the use of a new communication channel to better achieve the intended communicative effect.

Figure 1 User Interface for Dragon Quest VIII: a menu based on image icons from the English localized version (left) versus the Japanese original based on text (right)

This kind of practice is rare under current AVT norms, where diasemiotic translation (Gottlieb ibid.) – i.e. translation across different communication channels - is generally limited to the transfer from speech to writing, as in the case of subtitles, but normally not the other way around. The mode of audio description (AD) could be considered an exception, although its intended purpose is primarily different as it is designed to cater to the blind and visually impaired.

2. Changed character relationships and designs in the localized version

The next example is one of the few cases of a sim-shipped action RPG published by Square Enix. This game serves as a case in which the scope of game localization has been stretched in a number of areas. Released exclusively in Japan for PS3,

NierReplicant (2010) presents a story based on a sibling relationship, where the protagonist, Nier, tries to save his sister, Yonah. However, in the North American and European versions, NierGestalt (2010) released for Xbox 360 and PS3, the brother character was replaced with a much older adult figure as Yonah's father, with a completely re-designed character image, transformed from the somewhat androgynous depiction of the adolescent Nier to the more masculine father character Nier. Furthermore, NierReplicant was made Japanese-market exclusive, meaning only on the Japanese market were NierReplicant (on PS3) and Nier-Gestalt (on Xbox 360) both made available (see Figure 2). This departed from the standard approach to multi-platform games, where the same game is offered on different platforms, with Square Enix turning the formula into an opportunity to introduce a region-specific version. This new approach led to some pre-release confusion and debate, with some fan forum discussions extending to the issue of cultural specificity of Japanese games and international fans' desire to experience the original through an unadulterated version (Bailey 2009).

上一篇:Translator's Agency and Transcreation

下一篇:Taboo/Discriminatory Words in the Localization

微信公众号搜索“译员”关注我们,每天为您推送翻译理论和技巧,外语学习及翻译招聘信息。