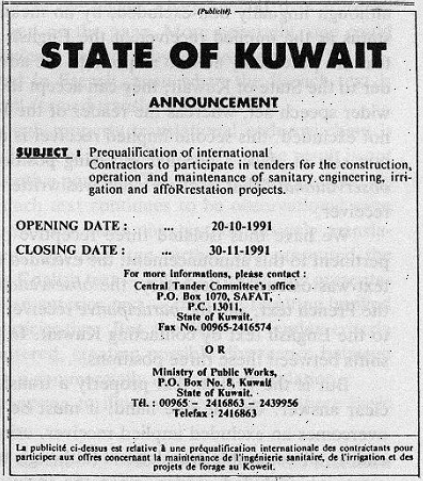

Figure 1. An advertisement from Kuwait

The French newspaper had presented the advertisement in English, and an anonymous official hand had added three lines of small print below, beginning “La publicité ci-dessus est relative à une préqualification internationale des contractants pour participer aux offres concernant…” (“The above announcement concerns an international pre-qualification of contractors to participate in tenders concerning…”). Why should the State of Kuwait have been speaking English in a French newspaper? Why should someone then tell us, in French, what had been said in English? What kind of localization was this?

Whatever answers we find to such questions (we shall propose a few), they mostly assume there is some kind of rationality at work in the distribution of texts and text-users. Those reasons are much harder to get at in the case of software localization, where there appear to be no people and no real movements involved. The software is anonymous technology speaking to anonymous markets; the newspaper advertisement seems to be doing something slightly more personalized. Hence the interest of trying to see the advertisement as a localization, and then trying to read that logic back into the mysteries of our computer.

Where did the advertisement come from? Let us go back to a moment prior to publication in the newspaper. Texts were moving. Perhaps a prince or minister's verbal reply to a question became an internal memo, then redrafted

by a finance department, sent through various hands in an external relations department, converted into publicity copy. Production itself surely involved complex distribution. Eventually, let us imagine, this multi-authored advertisement was sent from the Kuwaiti Ministry of Public Works to an international agent (where? in London?), then to newspapers all over the world. But also, later, in that sleepless hotel in Madrid, the announcement was still moving

through time, relentlessly approaching the closing date for pre-qualification (30 November 1991). And even now, if you think about it, that text is still moving, through time if not through space, as is the one you are reading at the moment. And we too are in movement. This is a world of moving texts and people, objects and subjects. Now, for all of us, it is logically too late to apply for prequalification. The participation once possible is no longer available. And near the end, when all the newspapers have been folded and filed away on microfilm or whatever, closed to all but the most inquisitive researchers, the Kuwaiti text will have reached a stage of dormant distribution, almost excluded from human observation, awaiting extinction with the final destruction of our libraries.

Our focus here must be on Le Monde itself, where all kinds of readers, editors, critics, and various translators were engaged in diverse aspects of localization. The distribution was given directionality, was partly directed, within the networks of a professional workplace. In that place, some of the incoming texts were going to be left as they were, some were destined to die in wastepaper baskets or faulty memories, others were to be shortened, still others were going to be expanded, and a few were going to be translated. Those decisions are not unlike the logics that make our computer multilingual.

责任编辑:admin

上一篇:Distribution Is a Precondition for Localization

下一篇:New Types of Translation Work Generated by Technology

微信公众号搜索“译员”关注我们,每天为您推送翻译理论和技巧,外语学习及翻译招聘信息。