2. Functional typologies

A number of functional typologies have been suggested, a few based on the notion of degrees of translatability but the majority organized on a three-way distinction (which derives from Bühler's organon theory of language; language as a tool5 depending on whether the major focus of the text is on: (1) the producer (emotive), (2) the subject-matter (referential) or (3) the receiver (conative). The typology we shall be discussing labels these distinctions (1) expressive, (2) informative and (3) vocative; the poetic, metalinguistic and phatic being, presumably, subsumed under the expressive, vocative and informative, respectively.

One advantage of this typology is that it makes it possible to list text-types under each function and, in the case of the informative function, distinguish 'topic' from 'format’. For example:

Informative; scientific textbook

Further, it is suggested that texts can be divided into three types – literary, institutional and scientific – but it is unclear under which function 'institutional' is intended to come and the problem of overlap still remains; 'scientific .. including all fields of science and technology but tending to merge with institutional texts in the area of the social sciences'.

What is still lacking is an objective statement of how the three types are to be distinguished without overlap and without an implicit dependence on native intuition. It is, after all, precisely this intuition which we wish to tap and to make explicit; it cannot, therefore, be 'given' in the argument, if we are to avoid fatal circularity.

3. Text-types, forms and samples

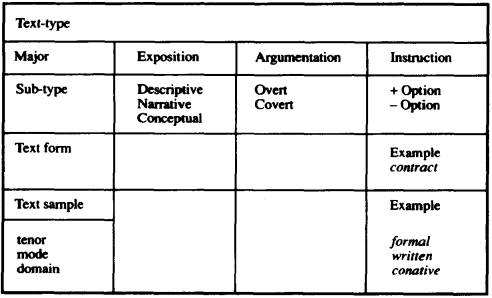

An extension of the three-way functional typology also proposes a three-part model: three 'major contextual foci, subsuming a number of others'. This model contains a number of features which are helpful in arriving at a more hierarchical model of text-types (which begins to address the type-token problem we raised above) and, in particular, in integrating with it the three major parameters of discourse variation. Figure 1 illustrates how the model works.

The first major category – text type – is arrived at by assigning to it a particular rhetorical purpose (alternatively, the type possesses a particular communicative focus) – exposition, argumentation and instruction – and each of these major text-types contains two or three subtypes:

Note: examples are in italics.

FIGURE 1 Text-types, forms and samples

Exposition: focusing on states, events, entities and relations and sub-divided into (a) descriptive; focus on space, (b) narrative; focus on time, (c) conceptual; in terms of analysis or synthesis.

Argumentation: focusing on argument, in a broad sense, either (a) overt or (b) covert.

Instruction: focusing on influencing future behaviour either (a) with option or (b) without option.

This gives a grand total of seven text-types (e.g. instruction without option) for each of which there are large numbers of text-forms (e.g. for the type 'instruction without option'; 'legal contract'), each of which can be realized as a limitless number of text samples – actual texts – which vary in accordance with choices from among the options available in discourse; tenor, mode and domain.

An example of this might be a legal contract which has selected from (1) tenor, formal, polite, impersonal, inaccessible, from (2) mode, single channel (written to be read), non-spontaneous, non-participative, public and from (3) domain; conative (and referential).

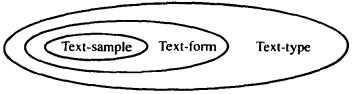

What this model provides us with is the same relationship of inclusion – type and token – which we found between proposition, clause and utterance. At text-level, we now have the equivalent:

4. Summary

The importance, from both a theoretical and a practical stand-point, of creating a comprehensive and plausible text-typology cannot be over-stressed. Without the ability to recognize a text as a sample of a particular form which is itself a token of a particular type, we would be unable to decide what to do with it; we could neither comprehend nor

write nor, clearly, translate.

We have considered, and rejected as excessively vague, formal typologies based on subject-matter, examined a three-way functional model which is not untypical of most current text-typologies and closed with a more sophisticated hierarchical model which seems to offer a more satisfactory framework for grouping texts and, therefore,

for specifying another element in the competence of the communicator (and, by definition, the translator). It is precisely to such communicative competence (the knowledge required for text-processing) that we now turn.

责任编辑:admin

上一篇:New Types of Translation Work Generated by Technology

下一篇:Benefits and Drawbacks of Working with a TMS

微信公众号搜索“译员”关注我们,每天为您推送翻译理论和技巧,外语学习及翻译招聘信息。