- 签证留学 |

- 笔译 |

- 口译

- 求职 |

- 日/韩语 |

- 德语

I am making the assumption that, by attempting to reconstruct the style of a text, the translator is attempting to reconstruct states of mind and thought processes, always with the awareness that individual states of mind are affected by social and cultural influences. Such an assumption plays an important role in stylistics and Critical Discourse Analysis, and is also behind the notion of faithfulness to style in translation, as suggested by Dryden's description of it as genius (Lefevere 1992:104) or Denham's as spirit (Robinson 2002:156).

The style of the source-text author, perceived as a reflection of her/his choices and mental state, will thus provide a set of constraints upon the stylistic choices made by the translator as an attempt to recreate this mental state. In the example from Kaiser & Holzman (2000) above, (c) might partly be seen as an expression of personality; in its use of a dialect word it suggests a certain informality.

A further set of constraints upon the translator's stylistic choices will arise from the function which a translation is seen to fulfil. Reiß & Vermeer (1984), as opposed to Reiß (1981), focus on constraints imposed by the target text: intratextual coherence in meaning and style of the target text is more important than the intertextual coherence between source text and target text.

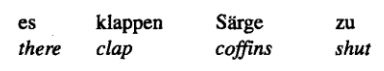

A particular choice of words by a translator may indeed aim for a documentary effect, for example by reproducing aspects of source-text style in a way which goes beyond merely reflecting the general use of stylistic principles. In my example from Kaiser & Holzman (2000) above, there was a conscious attempt to echo the sound of the German word 'beseitigen', even though this word was not actually used, and thus, in the informal English, to suggest the language of the original diary at least as much as a Northern dialect of the target language; in this sense that particular choice of words could be called documentary. But it is more difficult to apply such descriptions to a complete work. In this translation by Richard Dove (1996:48) of a line by Ernst Meister (1979:18):

coffins clapping shut

there is a strong echo of the original German

and for this reason the translation of this line could be called documentary, or more documentary than the more usual "coffins banging/falling shut". But the title of Dove's version of another poem in the same collection 'Maundy Thursday' for 'Gründonnerstag' (1996:15) would seem to be an instrumental translation: the English expression has been used to be consistent with an English cultural framework. A documentary title, like 'Green Thursday', would both reflect the cohesion of the source text built up in phrases such as grüner Saft des Lebens (green sap of life; Meister 1979:11) and Frühlingsacker (“spring fields; ibid.) and would recreate this cohesion in the target text. The only way to explain this apparent contradiction is to say that literary translation is to some extent documentary, but it is instrumental, too, in so far as the aim, as in Dove's translation of Meister, is to create a target text which works as communication between the source-text poet and the target-text reader. More than this, we could say that literary translation achieves its instrumental function (to be read as a literary translation) by being documentary (because this is what a literary translation does).

This view is very different from that of Nida & Taber (1974), who appear to feel that formal correspondence" is incompatible with dynamic equivalence". The latter, which is based on ensuring that the readers of the target text respond "in substantially the same manner" as the source-text readers, is more important. This means that stylistic subtleties" are only reproduced to the extent that they do not undermine dynamic equivalence (1974:14, 24, 13). Such a separation of style from effect appears to mark out the Bible as different from a literary text, in the view of Nida & Taber, and also as being different from a historical text, in which formal equivalence might be used for documentary purposes.

Because of Nord's discussion of documentary translation, it would not be true to say that all functionally-orientated theories of translation focus solely on the target text. However, such theories do share a common concern with the "social factors that direct the translator's activity" (Venuti 2000:216), a concern also of functionally-orientated views of style such as Fowler (1996). And yet functional translation theories such as Reiß & Vermeer (1984) or Holz-Mänttäri (1984) tend, oddly, to neglect the role of style, other than as an indication of text-type and therefore function (see e.g. Reiß 1976).

Nord (1997:120) shows that Reiß & Vermeer's skopos theory has been criticized for excluding literary translation because literary texts have no specific purpose (Munday 2001:81). And yet, in Nord's view, literary translations do have a purpose or function. This is particularly true of children's books and theatre plays, where the purpose of the target text is more important than the style of the source text, a situation which is likely to lead to domesticating translations (1997:83). In fact domesticating translations are made particularly when works are adapted for an audience very different from the original,such as Grimms'originally adult fairy tales translated for English children. As Kyritsi in an as yet unpublished dissertation has shown, translations of such stories, by consciously making the material conform to what is regarded as suitable for children at a particular time, can vary quite radically from the source text. In other translations such as the 1611 King James Version of the Bible (1939), which not everyone would regard as a literary translation, the purpose may also be an important determining factor. Such translations, in which both source text and target text are generally perceived as fulfilling a purpose, will be "covert", in the sense described by House (1981). They are not merely domesticating, but they tend to be read as originals.

What can be seen from discussions of the aim of translation, and the issue of documentary versus instrumental, and the relationship of both to literary versus non-literary translation, is that no clear distinctions can be drawn with respect to the attempt to recreate style. What can be said on balance is that:

i) no literary translation is purely documentary or purely instrumental;

ii) some literary translations are more instrumental and some more documentary;

iii) the style of the source text will be the greater determining feature for documentary translation and the style of the target text for instrumental;

iv) literary texts will achieve their instrumentality by being documentary;

they work as literary translations (are instrumental)partly by virtue of their relationship to the original (by being documentary).

The fourth point can be seen as support for the view that literary translation should be considered a unique type of writing within the whole range of literary writing. The fact that literary translation can only be instrumental if documentary also points to the main reason for its distinction from other types of translation: in other types the instrumentality is largely independent of their documentary relationship to the source text. Part of the reason for the combination of instrumental and documentary function in literary translation is that, if the notion of "literariness" is not as culturally-bound as Nord (1997:82) suggests, but is instead a universal form of aesthetic experience (as opposed to literature itself; Pilkington 2000:11-13), then documenting the literary nature and function of the source text would ensure that the target text is itself literary.This would mean it would be read as a literary text and allow for the sort of reader's interaction. In other words, if the intertextual coherence of the source text, which is the basis of its stylistic effect, is respected, the target text will, to the extent that it documents such effects, also work instrumentally.

责任编辑:admin