- 签证留学 |

- 笔译 |

- 口译

- 求职 |

- 日/韩语 |

- 德语

Each translator will have to decide for her/himself how much such knowledge of a poet's original intention can help in arriving at a meaning. One view is that the translator's reconstruction of what is inferred as the poet's intention is actually more helpful, because it is the role of the translator as reader of the original text to make such inferences. Expressed in Relevance-Theory terms, this means that the translator's inference that unbound means 'released', derived from evidence in the style of the text, leads him to assume that the implications in the style giving rise to this inference are in fact implicatures or intended implications. Whether they were ever actually intended is irrelevant. The point about a stylistic reading of the source text is that it aims to reach a full and detailed picture of the inferred author's choices, not that it can or wishes to reach facts about an actual author's choices.

Does, for example, the choice of the word "verschollen" (disappeared) in a poem by Rose Ausländer suggest the agency of an evil government? The translation by Osers as long-lost" does not carry this implicature (1977:47), but today's reader would almost certainly read such an implicature into the German word, and thus be more likely to translate it with 'disappeared'. Are we to say this connotation is consciously or unconsciously motivated in the original poem, or is put there by the reader?

If, as MacKenzie ( 2002:30) explains, pragmatic approaches to the reading of literature always take for granted the importance of human agency in its production, then this also applies to pragmatic views about reading, including the translator's reading of the source text. A pragmatic view also takes for granted that a translator is not just a reader, but also a communicator, and that the aim of a translation therefore goes beyond the mental expansion and cognitive pleasure of the translator because s/he will try, in the target text, to make choices potentially able to give rise to effects on target-text readers which reflect the potential effects of the source text on its readers. The writer of the translation is thus initially responsible (to the extent that any of us can be responsible for unconscious linguistic motivation) for the style of the translated text to which the reader responds and from which s/he will create meaning; it is the translator in her or his role as writer who "triggers discovery in the reader" (MacKenzie 2002:24). As Sperber & Wilson (1995:8) put it, the text does not restrict the meanings it is possible for the reader to construct, but it does "impose some structure on experience, guiding or even manipulating her or him in ways which are often not obvious.

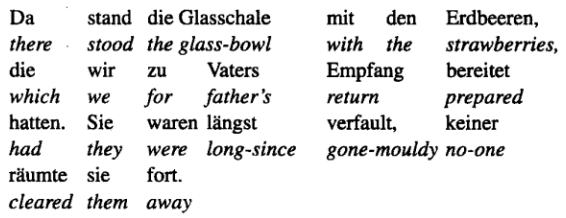

Choice, whether seen as more or less restricted, has always been a central issue for stylistics. A typical definition is given by Thornborrow & Wareing (1998) at the start of their introductory book on literary style: stylistics, as the study of style, tries to account for "the particular choices made by individuals and social groups in their use of language" (p.3). This definition, taken from the Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (1977), provides a common denominator for a whole variety of ways of approaching style, and elaborates upon the notion of distinctive" in the Wales definition. Distinctiveness arises because of choice exercised by a writer. Enkvist et al (1973:16-17) maintains that style is the variation within a language based on optionality, and so differs in this respect from regional or social dialects, and also from the rules and principles of grammar about which we have no choice (see also Vinay & Darbelnet 1995:16). Because choice can be exercised in the realm of the second-order meanings, rather than in those meanings determined by lexis or syntax, style will affect such second-order meanings. For a translator, style is possibly the least contentious area of translational freedom. Consider, for example, the following sentence from Helene Holzman's diary (Kaiser & Holzman 2000:25):

Looking at the final phrase "keiner räumte sie fort", there appears to be clear evidence from (primary) meaning to guide a choice in translation between, for example,no-one hid them away"and no-one cleared them away". The first introduces meaning that is not merely a stylistic variation from the sense of the original, and would generally not be considered a translation of the phrase. The second, however, is close in meaning to the original. But it is related by stylistic as opposed to lexical-semantic variation to several other possibilities:

a) no-one cleared them away

b) no-one moved them

c) no-one sided them

d) no-one thought to throw them away

e) no-one took them away

All of these alternative versions in some intuitive sense mean roughly the same. Stylistically, (a), (b) and (e) are similar; (c) is different in that it introduces a dialect word; (d) uses alliteration. On the face of it, then, these might seem stylistic variations about which the translator, even by conservative standards, has plenty of freedom. However, it is not so simple. (c) is an authentic example; I used it in a sample translation of Helene Holzman's diary for at least two reasons. Firstly, I wanted both to suggest something of the colloquial nature of the original text, a diary (even though at this particular

point the original was not colloquial: forträumen is fairly formal). But, secondly, I also wanted to echo a possible German alternative to the original: beseitigen – 'to clear away'; literally 'to put aside', 'to side').There was also a third, more personal reason, too: in the photographs, Helene Holzman, the writer of the diary, reminded me very much of my grandmother, and she used to say to side". But the editors of the sample did not like it, and changed it to (e).

What this example shows is that the style we choose as translators is subject to all manner of constraints and influences, some of which the translator may only be dimly aware of. In the rest of this section I will consider the sources of such constraints and influences before moving on, to look at some of the ways translators'stylistic choices and the constraints on them have been theorized and, in 3.3, at some of the ways the analysis of style in the target text has tried to recreate the sort of choices made by the translator.

Style, then, is seen in most stylistic approaches to texts as a question of (sometimes unconscious) choice. But it is not just choice of words or structures or sounds. According to Fowler, the concept of style goes far beyond this: it includes language in and outside literature, and "non-linguistic communication and other behaviour" and is therefore "unusable as a technical term" (1996:185). "Style" has indeed many areas of application, but style in language refers to those aspects of language assumed by the hearer, reader or translator, and indeed by the speaker, original writer, or writer of translations, to be the result of choice.